Tags

annotating, Ezra Pound, John Keats, jottings, Kafka, Kubrick, marginalia, Mark Twain, Mark Wain, Medieval illuminated manuscripts, Metamorphosis, Nabokov, Scholia, Stephen King, Sylvia Plath, The Annotator, Token Magazine, TS Elliot, William Blake

My new short story, The Annotator, is published by Token Magazine this week and is available now from http://tokenmagazine.bigcartel.com/

Well, that’s the advert over!

But, as this blog is all about the contexts of writing, I thought my reader (I know who you are) might be interested to know how the story actually came about.

As usual, for me, the inspiration came from something I had been reading – in this case Vladimir Nabokov’s rather brilliant Collected Short Stories. Being an impoverished pensioner, I had borrowed the book from the library, and, as I read, I began to notice, with initial irritation, the jottings and annotations in the margins and page gutters that had been made by a previous reader. However, after a while, rather than seeing these marks as intrusions, sending me over the edge with irritation, I began to find the neat underlinings, the ticks and crosses and the words ocassionally inscribed, strangely interesting. They began to form, as it were, a kind of coherent dialogue in my head.

It was this that gave me the idea for a story about what might occur if (in my protagonist’s case) a slightly unhinged reader of the stories (not me, honest) felt that there were hidden messages to be found in the annotations made by the other reader. As can be seen in this extract:

“In the Nabokov, under the cover of his voice as soft as moth wings and as cold and velvety as falling Christmas snow, there was a kind of silence in which I could hear the increasingly clear comments, admonitions and orders of the Annotator.”

And then, I began to wonder, what if my character should act upon these “orders”?

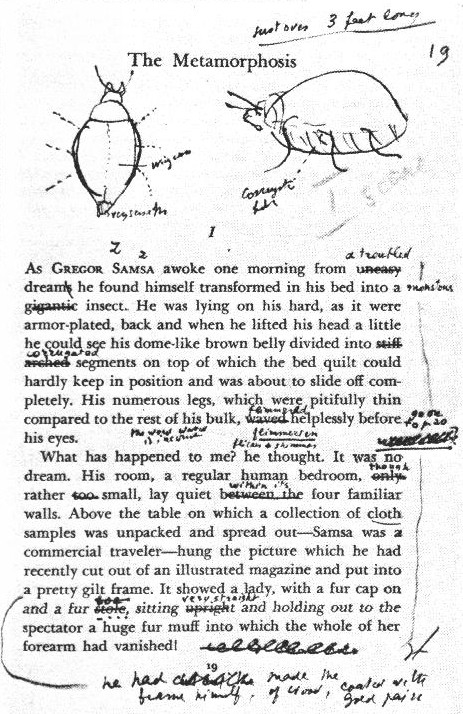

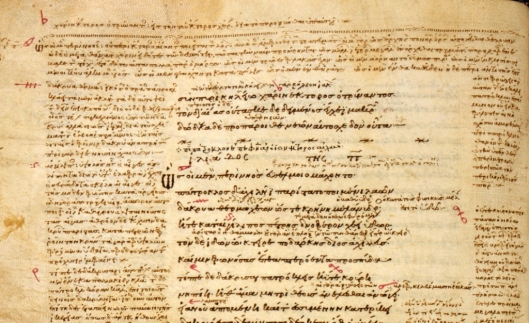

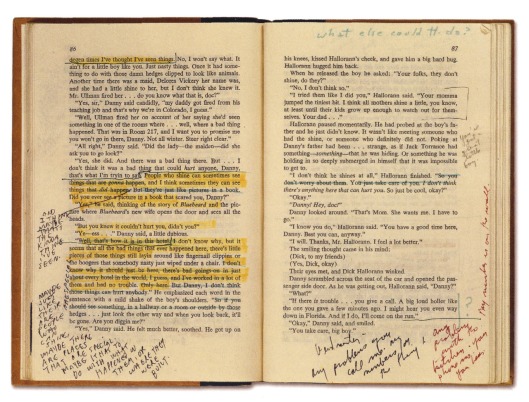

This started me thinking about the whole business and purpose of the annotation process itself – the marginalia, underlinings, scribbles and jottings that have been made in books generally. What is particularly interesting, of course, is to look at those annotations made in literary texts read by famous writers. Here, for instance, is a page of Nabakov’s own annotations (or corrections) to a translation of Kafka’s Metamorphosis.

This is not just underlining, jotting or doodling but a thorough and intense interrogation of the text. Here, Nabakov brings to his reading all of his extensive knowledge as an entomologist and as a linguist. Not only does he illustrate the creature that Kafka’s protagonist might be turning into but he corrects or suggests a better translation for some of the words used: replacing, for instance, “stiff arches” with (I think) “corrugated”.

Jottings like this, both trivial and profound, have, of course, a very long history. They date at least from the Scholia (ancient commentaries or annotations) made in the original texts of Homer’s epics – the Iliad and Odyssey – the earliest of which were made in the 5th or 4th century.

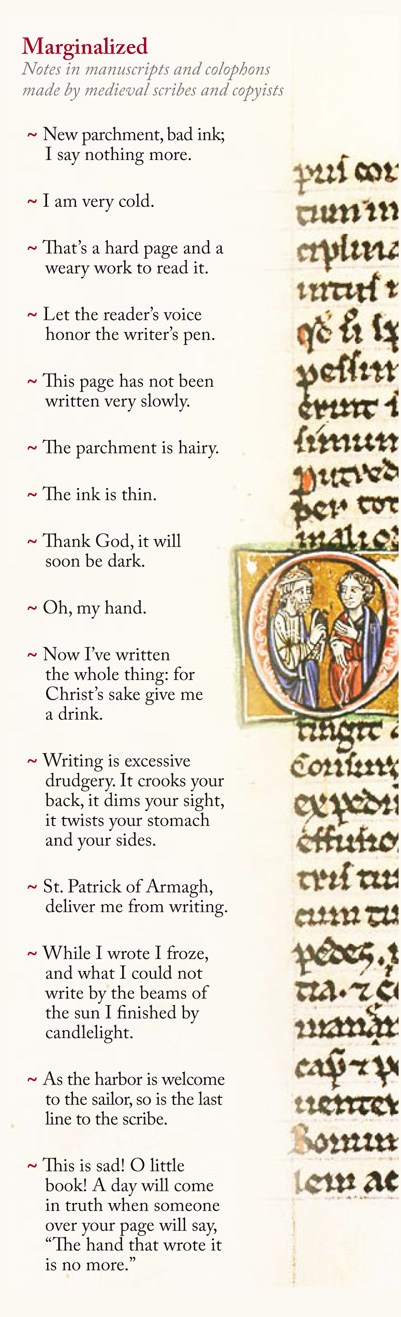

More amusing than these scholarly annotations, however, are the beautifully scripted marginalia inserted by worn-out medieval monks as they laboured for hours on end on illustrated manuscripts.

Amongst these we can find examples such as the following priceless off-task asides:

“Oh, my hand!” and “Now I’ve written the whole thing: for Christ’s sake give me a drink!”

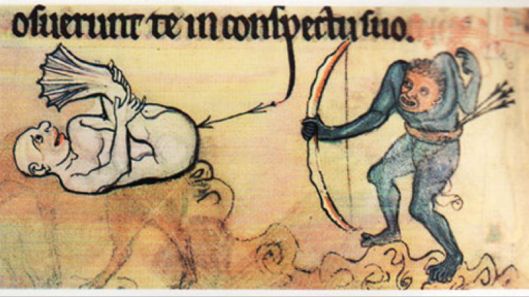

Even the pictorial marginalia in these fantastically illuminated texts are clearly more, much more, than casual doodles. The images, as well as being extravagantly bizarre, may well be intended as a witty, if elusive, commentary on the text itself. They are made (if the written annotations I have mentioned above are any guide) by bored and often shockingly irreverent monks / artists, amusing themselves and taking the opportunity to express their outrageously anarchic imaginations.

They contain such outlandish images as the flying penis monster above, as well as being sprinkled expansively with many other miscellaneous monsters, such as giant snails and nightmarish executioner rabbits/hares.

Although the exotic marginalia in these illustrated manuscripts are comprehensively imagined there is occasionally something that might be as spontaneous as a simple doodle, as, for instance, in the image above, where the arrow flying into the demon’s arse seems an impromptu extension of an individual letter of the alphabet.

A scribbled word or a doodle in a book does not, though, normally result in a thing of quite such beauty as the marginalia in an illustrated medieval manuscript. However, though frowned upon by librarians, these comments and doodles, idle or impassioned, may have a number of different and interesting effects upon the next reader: irritation being one, as well as annoyance that somebody is defacing a publicly owned book and distracting us from the text itself. But it can also be interesting to see what other readers are thinking about a text at the very moment that they, like you, are reading it.

A scribbled word or a doodle in a book does not, though, normally result in a thing of quite such beauty as the marginalia in an illustrated medieval manuscript. However, though frowned upon by librarians, these comments and doodles, idle or impassioned, may have a number of different and interesting effects upon the next reader: irritation being one, as well as annoyance that somebody is defacing a publicly owned book and distracting us from the text itself. But it can also be interesting to see what other readers are thinking about a text at the very moment that they, like you, are reading it.

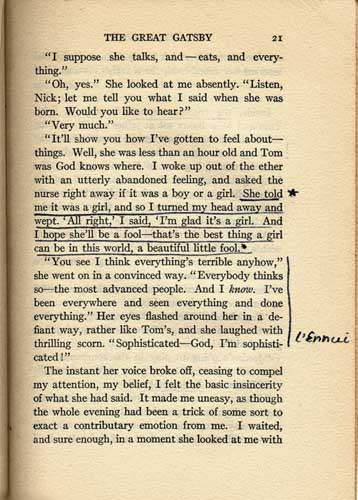

Many a school or university literature student has been very grateful, I’m sure, to read somebody else’s thoughts on a text – thoughts that they can then insert into their next coursework essay as if the insights were their own. (Although if you stumbled on Sylvia Plath’s copy of Fitzgerald’s Great Gatsby, above, you’d still need to do a lot of interpretation for yourself.)

The annotation of a text is actually a sort of dialogue with it and a number of possible conversations might be occurring when somebody scribbles a note or marks a section of text in a book. The first, I suppose, is the dialogue with self. What fun, what splendour and what embarrassment there is to be had by reading, as an older person, some comment one has made as a callow youth on a central text of the English literature canon!

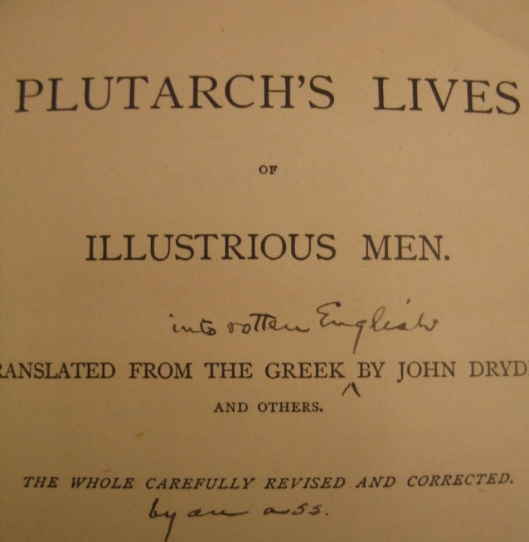

The second and third conversations, however, might be with the writer of the book or with other (known or unknown) readers of the same text. This might be an argument, a criticism or a commendation. Or perhaps an insult. Mark Twain, here, for example, was clearly quite annoyed by Dryden’s translation of Plutarch’s Lives, calling the poet and playwright “an ass”.

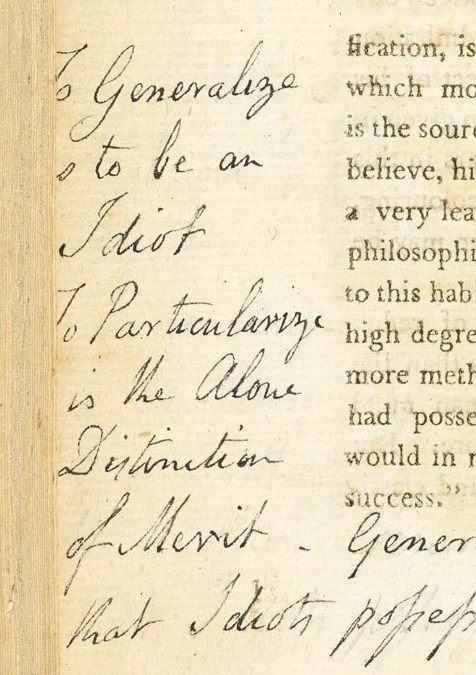

William Blake, like Mark Twain, was a prolific annotator of texts and equally as free with his insults. Blake is famously furious, for instance, here below, with the artist Joshua Reynolds. He argues with him from the off (through his annotations of The Works of Reynolds) in an angry (if delightfully florid) hand, that “to generalise” (one of the virtues of Reynolds’ work vaunted by his editor) “is to be an idiot.”

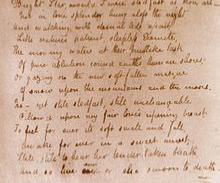

Annotations, especially extended ones, may, however, result in more than insults or what might be called, at their best, philosophical disagreements. They might also result in a work of art in themsleves. John Keats, for example, yet another prolific annotator, had his copy of Shakespeare’s Poetic Works passed on to him by fellow poet and friend J.H.Reynolds. This text shows a dialogue (to be found in the margins) between the two poets about Shakespeare’s artistry. However, the outcome, even more wonderfully, and drafted alongside the text, is the first version of Keats’s lovely Bright Star poem, presumably inspired by what he was reading.

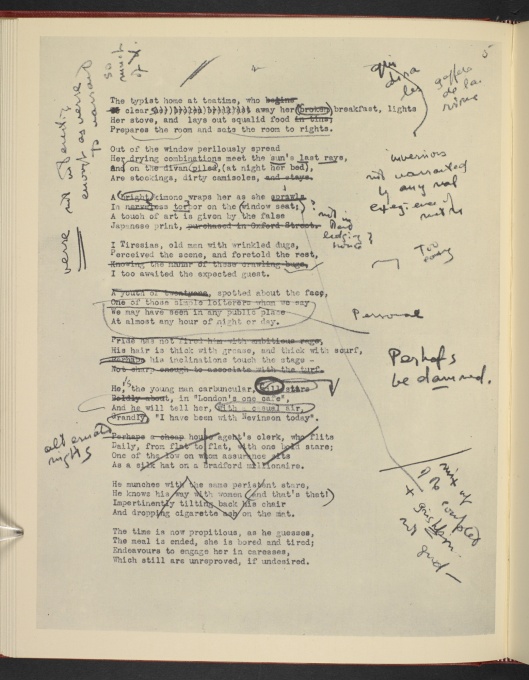

Artists and scholars will of course annotate a text for very different and specific purposes. Ezra Pound, for example, famously annotated a draft of T.S.Eliot’s Waste Land, cutting it down to almost 50% of its original size in the process. He made no bones about what he approved or disapproved of, as can be seen in his aggressive slashed crossings-out. I particularly like Ezra Pound’s irritation with Eliot’s use of the equivocal “perhaps“. “Perhaps,” as he says, “be damned”.

Stanley Kubrik’s annotations, seen throughout his copy of Stephen King’s The Shining, clearly also has a specific editorial purpose as well as a filmic focus.

The actual annotations in the copy of the Nabakov I was reading and which inspired my own story, as I’ve said, were no more than ticks or crosses, odd words (“good”) or glosses on unusual words (“furunculosis = boils”). I imagined, though, that my protagonist in The Annotator was mentally unstable – a condition that, like Jack Torrance’s in The Shining, is exacerbated by his sense of isolatation and, in my protagonist’s case, by the breakdown in his marriage. Where Torrance begins to see visions, my character hears loud voices – in his case the voices of the authors of the books he reads. These voices, for him, take on an alarmingly visceral kind of reality:

“If I opened Paradise Lost, Milton explained man’s first disobedience to me as if he were whispering directly into my ears there and then. I could smell the metallic tang of his blind eyes and the blood in his piss. When Coleridge chanted his poems to me I could taste the laudanum on his breath and smell the nappies boiling in the wash-tub at Nether Stowey. Dickens spoke to me as his most intimate friend – whilst he imbibed his opium tincture I could feel the Addison’s tremors convulsing his cheek and neck.”

Eventually these voices, powerful as they are, give way to the more immediate voice of the annotations in the Nabakov. A voice that eventually becomes all powerful. The annotations in the collection of Nabakov’s short stories that he reads become voices that send him, finally, over the edge.

A far cry, admittedly, dear reader, from merely underlining a word in a text!

As you might know (where have you been?) I’m the writer of Inspector Bucket and The Beast –

As you might know (where have you been?) I’m the writer of Inspector Bucket and The Beast –