Tags

Born on the 4th July, Captain Ahab, Disabilities, Double Indemnity, God, Illness as metaphor, Inspector Bucket and the Beast, Inspector Bucket and the Olympics, Limping, Matthew 15, Meniscus tear, Old Testament, Redemption, Shaun of the Dead, Sherlock, Sumerian texts, Susan Sontag, The Annotator, The Usual Suspects, Token Magazine, Wrestling with God

‘For no one who has a defect shall approach: a blind man, or a lame man, or he who has a disfigured face, or any deformed limb. (Leviticus 26.18)

For nine months I have been a lame man: a limping man. Meniscus tear, don’t you know – for which, back in January, I had arthroscopy of the knee. I’ve had nothing but sympathy, of course, during this time, but my crab-like gait has put me in a brotherhood (and sisterhood) of people who have (or have had) a gammy leg – and worse. We are legion, we limping men.

Yet in films and fiction and ancient lore we, the limping people (crippled by arthritis, Achilles’ tendon injuries, twisted ankles or dodgy knees, on crutches, in plaster casts, missing a limb and in wheel-chairs – temporarily or permanently) are, as often as not, seen as objects of suspicion, omens of evil, ripe for mockery or an easy target for abuse or exploitation.

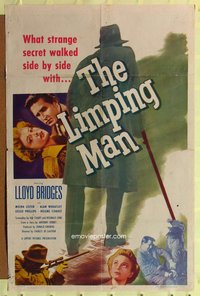

From the limping man, in the eponymous British noir thriller (The Limping Man) to limping, weaselly con-man Roger Kint in The Usual Suspects, the man with the limp (as I shall call those who are temporarily or permanently disabled) is presented as a figure of menace or ineptitude. From The Day of the Dead to Shaun of the Dead, it is the lurching, limping man (woman or child) shuffling towards us that establishes a sense of mockery or impending terror.

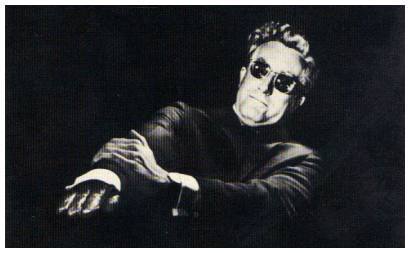

Amongst the multitude of the disabled, one might mention evil Captain Hook with his hooked hand; the hobbling and dangerous Long John Silver; manic Dr Strangelove (in his wheelchair with his deranged mind and uncontrollable Nazi salute); Captain Ahab, limping along the foredeck in Moby Dick with his peg-leg and epic desire for existential revenge; even the poor put-upon but hapless Mr Nirdlinger in JM Cain’s Double Indemnity – whose murder the reader or viewer feels is somehow justified.

All lurching, shuffling, limping men.

What all this is about, of course, is not a malicious prejudice against us limpers but, as I have discussed in one of my earlier posts (and as Susan Sontag famously argues in her essay ‘Illness as Metaphor’) another example of writers using disability as a metaphor for character. The correlation is clear: if a character in fiction is wicked, morally compromised or challenged in some way, he is likely to be pre-marked with a physical affliction. At the best he might rise above his physical disability to show himself morally renewed; at the worst, he must be seen to be punished for his evil, an evil so obvious in both his inner and outer nature.

Giving a man a limp is, at the very least (notwithstanding its metaphorical overtones), a way of making a character, as Doc Henshaw argues in one of his on-line creative writing sessions, “interesting”. This idea is one of the standard clichés of creative writing classes. Henshaw boasts of being able to list thirty-four limping characters from literature, film or TV, and all within the space of fifteen minutes. (Quite a party trick!) He includes Chester’s twisted gait in Gun Smoke, Dr. Philip Carey’s lurch from W. Somerset Maugham’s Of Human Bondage, Dr. Weaver’s tapping cane from the TV show ER and Dr. Watson’s “psychosomatic limp”, as seen in the first episode of Sherlock. (An interesting grouping of Doctors there!)

The disability, however, doesn’t have to be a limp, it is obvious to state. Henshaw himself begins by recommending to a student that he make a character deaf to make them more dramatically appealing. It could be a missing arm, as with the infamous one-armed man in The Fugitive; Jamie Lanaster’s golden prosthetic hand in Game of Thrones, or John Wayne’s/Jeff Bridges’ eye-patch in True Grit.

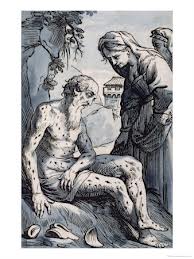

In the bizarre biblical story of Jacob wrestling with what most commentators agree is God, Jacob himself ends up as a limping man. Although Jacob seems to win the bout, God’s parting shot is to dislocate Jacob’s hip. The price of seeing (and wrestling with) God face-to-face is apparently to be blighted with the mark of the limping man.

In my capacity as a god-like author who is in control of my characters’ fates, I confess to using this trick myself: of metaphorically and actually disabling my characters. In my novel, Inspector Bucket and the Beast, I curse the morally suspect Frederick Dreadnaught with small-pox, and in one of my ‘Inspector Bucket’ short stories, Inspector Bucket and the Olympics, a character uses the fact that he is on crutches (another limping man!) to attempt a desperate fraud. In The Sad Strange Tale of Jon Bergersson I handicap my eponymous hero with ‘sickness’ and ‘asthma’. And in my experimental steam-punk story, Moriarty’s Revenge, I curse the moral coward Markham, who partially narrates the story, with both a limp and a glass eye – double metaphorical imperfections! I might also have taken the opportunity to give the rather psychotic protagonist in my The Annotator, (due to be published in the first print edition of Token Magazine on the 1st May) a physical imperfection – but I resisted. Perhaps hearing voices that he feels are controlling him, or at least prompting him to certain actions, is already enough of a handicap: a kind of limping in its own way.

There are precedents for all this (as always, and as I have already implied) in the Bible. The Author of All Things easily outdoes us earthly authors in the way He seems so shamefully happy to blight those who offend him – and with the most terrible of infirmities too:

“The LORD will smite you with madness and with blindness and with bewilderment of heart. (Deuteronomy 28-9)

He seems equally happy (smug almost) about accepting the blame (or praise) for causing the disabilities in the first place:

“The LORD said to him, “Who has made man’s mouth? Or who makes him mute or deaf, or seeing or blind? Is it not I, the LORD?” Exodus 4:11

Thus, the blueprint for the metaphorical use of the limping man is deeply embedded in the Bible itself where, as Jeremy Schipper argues, disability, more often than not, is seen as a religious, moral or theological issue under the control of the divine (as at Gen 16:2; 20:18; 25:21; 29:31; Exod 4:11; 23:26; Deut 7:14; Judg 13:2-3; 1 Sam 1:5; 2 Chron 16:12).

Christian commentators often use the Jacob story to show how when mankind gets too cocky about himself, God will put him in his place. The key quote here seems to be from Psalms 147:10-11: “God does not delight in man’s strength or cleverness, but in those who fear Him and put their hope in His unfailing love”

Thus God cripples Jacob. Seems like a low blow to me. And after the bell too, for Jacob had clearly won the bout.

However, in a turn-around to my central point, I must concede that some Christians advise us not to, “trust a man without a limp.” The idea here being that a man who doesn’t realise he is nothing without God, and that he is dependent on the Lord just as a crippled man might be dependent on his crutches, is a lost man.

Nevertheless, what we are seeing here, once again, is how disability is being used as a signifier of a moral condition.

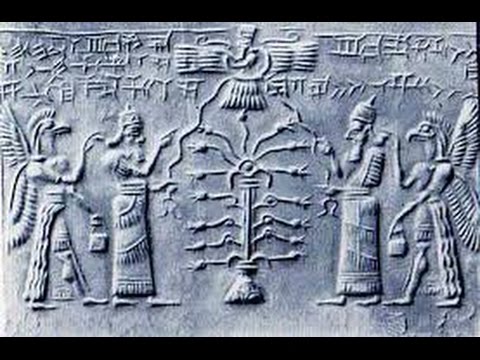

However, this moral attitude to the limping man goes back even earlier still than the Hebrew Bible, to, arguably, the most ancient of ancient texts. The first tablet of the earliest extant Sumerian prophetic texts predicts, we are told, the danger to ancient society of contact with a limping man:

“If a woman gives birth to a limping male : penury”

Another tablet reads, with even more confidence, that, “If a woman gives birth to a cripple, the land will be disturbed; the house of the man will be scattered.”

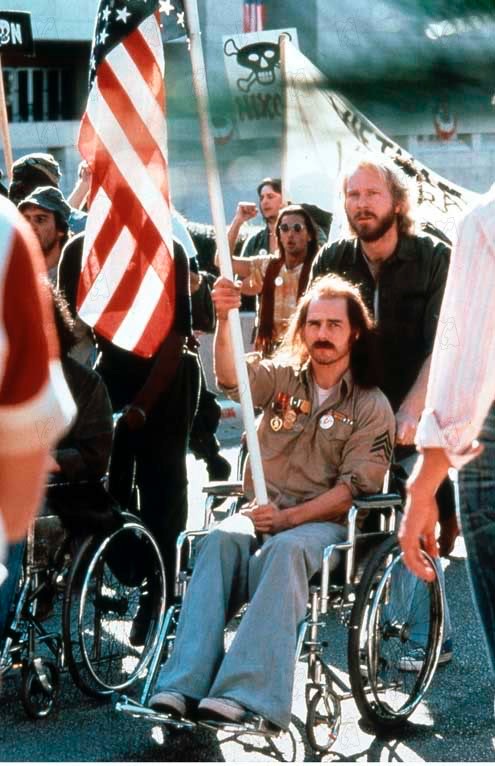

Modern narratives, however, when not turning the limping man merely into an object of menace or bitterness, do sometimes present the possibility of redemption through disability. We see this, for example, in Ron Kovik’s Born on the 4th July (film directed by Oliver Stone) where, by the end of the narrative, the wheelchair bound Kovik attains, it seems, a form of both political and moral regeneration.

The Christian New Testament, too, it is fair to say, in its use of disability metaphors, focuses (in contrast to the Old Testament) just as much on the redemption of the sick and the lame as on the disabilities themselves. It employs both figurative language and the actuality of disability itself to suggest that the limping man may one day be restored to transcendent moral and actual health:

“And large crowds came to Him, bringing with them those who were lame, crippled, blind, mute, and many others, and they laid them down at His feet; and He healed them. So the crowd marveled as they saw the mute speaking, the crippled restored, and the lame walking, and the blind seeing; and they glorified the God of Israel.”

Matthew 15

A fantastically moving passage, of course, and yet I find it hard to believe that this redemptive God of Israel is the same deity who clearly seems to relish causing the disabilities that afflict mankind in the first place.

As for me, the operation (you’ll be pleased to know) was successful – although I confess a residue of the limping man returns to haunt me if I become way too cocky in my walking!

Nevertheless, this limping man is back to walking a less crooked path – at least physically.