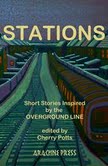

With Arachne Press due to publish its Stations Anthology (arachnepress.com/books/stations) wherein dear old Inspector Bucket has another outing in my story Inspector Bucket Takes the Train (dealing with devious thieves on the Highbury and Islington line) it’s time to blog about trains and their place in Dickens’ writing!

With Arachne Press due to publish its Stations Anthology (arachnepress.com/books/stations) wherein dear old Inspector Bucket has another outing in my story Inspector Bucket Takes the Train (dealing with devious thieves on the Highbury and Islington line) it’s time to blog about trains and their place in Dickens’ writing!

So what did Dickens think about the train?

Despite the fact that the railway age had started in 1830 (when he was already 18) it might seem that Dickens, like my version of his character Inspector Bucket in Inspector Bucket Takes the Train and Inspector Bucket and the Beast, had no time for the train. Perhaps he too might have

“preferred to see the streets and the alleys and courts of London as he rode along – not just the backside of factories.”

In the popular imagination Dickens is probably mostly associated with the coaching age, the era of the horse and carriage and of coaching Inns. And with good reason.

Dickens’ first novel, ‘Pickwick Papers'(1836/7), is, of course, about the very business of ‘coaching’, describing the Pickwick Club’s adventures as its members journey through Regency England, just prior to the railway age. Though serious themes are dealt with and though some encounters with coaches and coachmen are sometimes angry ones, the associations linked with the idea of coaching are invariably to do with being “hearty” and “easy” , and of rolling “swiftly past fields and orchards”. Despite some of the novel’s darker elements its tone might be summed up in this description:

“The coach was waiting, the horses were fresh, the roads were good and the driver was willing.”

Similarly, In 1840, when Dickens began ‘The Old curiosity Shop’, although both London Bridge and Euston Railway Station had been open for nearly four years, Dickens was still enveloped in nostalgia for the old coaching days:

“What a soothing, luxurious, drowsy way of travelling (it is) to lie inside that slowly-moving mountain, listening to the tinkling of the horses’ bells…”

The sleepy lyricism of this contrasts with an early description of a railway engine from ‘Pickwick Papers’ (1836), treating the train as an object of comic ridicule:

“a nasty, wheezin’, creakin’, gaspin’, puffin’, bustin’ monster, alvays out o’ breath, like a unpleasant beetle … alvays a pourin’ out red-hot coals at night, and black smoke in the day…”

Curiously, apart from this reference, the train seems to play little or no part in any of Dickens’ first five novels. In ‘Martin Chuzlewhit’ (1843), the sixth,it appears at last, (though in an American incarnation) transformed from something whimsically comical into something much more agonised, with an

“… engine (that) yells as if it were lashed and tortured …and (that) writhed in agony.”

Clearly some of Dickens’ later novels though written in the railway age are set before it – whether it be the horrors of the French Revolution, as seen in ‘A Tale of Two Cities'(1859) or in the nostalgia of Great Expectations, begun in 1860 but clearly about a world mostly stuck between 1812 and 1830. But those novels that are set in a contemporary world see the train as something destructive or presaging something hopeless or catastrophic.

In Dombey and Son (1846-8), for instance, the building of the railway is described as “an earthquake” which “rent the neighbourhood to its centre.” It is compared to “the track of the remorseless monster, Death!” But it is also seen as an an agent of avenging justice when the novel’s villain James Carker is run over by a train and “mutilated” so that his split blood has to be “soaked up by a train of ashes”. In ‘Our Mutual Friend'(1864/5) a train “shot across the river, bursting over the quiet surface like a bomb shell.” Here we have the continued metaphor of the railway age as despoiler of the natural world but Dickens also seems to imagine the railway as a metaphor for a despoiled society – as in ‘Bleak House’ ((1852/3) where, because of the railway, “everything looks chaotic and abandoned in full hopelessness“. In ‘Hard Times'(1854) the metaphor is extended to despoiled or diseased human beings, where the arrival of a train gives rise to “the seizure of the station with a fit of trembling, gradually deepening to a complaint of the heart…”

Although Dickens’ final (unfinished) novel, ‘The Mystery of Edwin Drood'(1870), is written at a time when most of the major Victorian railway stations were already built and the railway age was in full bloom, Dickens chooses to return to the nostalgia of his almost railway-less youth in Rochester, where, significantly, the railway station in imaginary Cloisterham is “unfinished and undeveloped”. In fact, we are told, “… the trains don’t think Cloisterham worth stopping at.” Actually, Dickens had bought his childhood dream house in Gad’s Hill, Highham, Rochester, (the model for Cloisterham) in 1857, using it as his country retreat and dying there in 1870. It is inconceivable that the endlessly moving, the endlessly travelling, Dickens would ever have lived in Higham at all if there hadn’t been a railway station with a good connection to London, what ever he may have felt about the railway in other ways. Indeed, in her biography of Dickens (Charles Dickens – A life), Clare Tomalin speculates that on the very day he died Dickens may have taken the train (and cab) from Higham Station (a mile from his house in Gad’s place) to Peckham in South London where he regularly paid the housekeeping for his lover Nelly Ternan.

It was Nelly Ternan, too, who was with Dickens on the day of the Staplehurst train disaster, the 9th of June 1865, when the train to Charing Cross hit a bridge and fell into the river below. Ten people died and fifty were injured. Dickens almost lost the manuscript of his last completed novel, ‘Our Mutual Friend’. Dickens famously went to help his fellow passengers with, according to Clare Tomlinson, “his brandy flask and his comforting and practical presence.” But he made sure that his lover, despite injuries to her arm and neck was, according to Tomalin again, “discreetly and hastily removed from the scene before anyone could become aware that (she) had been travelling with Dickens.” Clearly Dickens was, unsurprisingly, “shaken” by this experience and we are told, in a remembrance of him by one of his sons, that “.. sometimes in a railway carriage when there was a slight jolt…he was almost in a state of panic and gripped the seat with both hands.”

Although there is much in both his life and work advocating the railway for its economic and practical advantages, as well as demonstrating the pleasure to be found in train travel itself (as in his journalistic piece ‘Flight, 1851), in his novels and some of his shorter fiction (such as ‘Mugby Junction’ and ‘The Signalman’, both 1866) the railway remains an issue of anxiety and an image of foreboding darkness.

The final irony is that Dickens died on the fifth anniversary of the Staplehurst disaster and that his final, funereal journey from Higham to London and Westminster Abbey was, of course, via Charing Cross Railway Station – by train.

Dickens liked the denizens of the streets and they so much a source of his creativity. Trains have changed and highways aren’t as romantic. I thoroughly enjoyed reading your post.